Fundraising 101: Negotiation

This is the fourth installment of five part series on tactical guidance for Seed fundraising. This series was originally written by me during my tenure at Entrepreneur First and can also be found here.

The weeks of sleepless nights, endless coffees and bruised egos seem to evaporate with a term sheet in hand. Celebration is certainly in order so take the night off—but tomorrow it’s back to work. Getting a term sheet is far from the end of your fundraise. Now is the time you get out of tactical execution and start thinking big picture.

Not all term sheets are created equal, and it’s all on you to figure out if your offer is a tool for growth or a bill of goods. In this post we’ll cover a range of contradictory aspects you’ll need to consider before signing a term sheet. Focus on the drivers of long term. Ignore vanity metrics. Your work isn’t done yet, but you’re getting close. If you can keep a cool head this will be really fun.

Raise what you need, not what you want

It’s not uncommon to hear “we believe in you, but you need to be raising more.” This demonstration of conviction can be very flattering for a young founder, but remember every coin has two sides. What may seem like alignment on your growth plan is likely driven by an investor’s fund economics. I’ll avoid the finance specifics but in short, investors need to put their capital to work, and very small checks don’t make sense (relative to the total fund size). You don’t see £500M+ funds writing checks for less than £500K because the return potential doesn’t justify the effort. If, however, you could push that investment to £1.5M, then perhaps the math works out. “Cash Raised” should be dependent on what your individual business needs. Most argue that you should raise for 18 - 24 months of runway. Raising too much can be as damaging as raising too little, so I usually suggest sticking with 18 unless you’re very deep tech and really need time to build sales. A little fear will keep you scrappy. If you think you can legitimately accelerate growth, make better hires, etc. then increasing your round may make sense. But if an increase feels like an over-capitalization, just keep the investor relationship going and find a backer that’s more attuned to your current stage.

Valuation doesn’t matter, dilution does

At the earliest stages a valuation is little more than a formula influenced by subjective variables. There are two equations that you need to know:

1. Post-Money Valuation = Pre Money + New Cash Raised

2. Post-Money Valuation = New Cash Raised/New Dilution

Post-Money is just an output, and you’ll find most investors typically focus on Pre-Money. Of course investors want to purchase equity at a cheaper price because it’s easier to yield a return from a lower starting point. What they’re really focused on, however, is ownership. Remember: investor ownership = founder dilution, so those few percentage points may not seem like a lot now, but they will in the future. As a rule of thumb you should assume every early stage round will dilute management by 15-25% and later rounds might be closer to 10%. If you can get better than this, great, but there are market norms. The point is there are natural limits to how much you can give away in a given round. A $10M Seed round will sound great in TechCrunch, and you’ll probably be able to get a sweet office, but if it cost you 40% then you’ve also f**ked your company. Giving away too much in a deal shows immaturity, poor business acumen and creates management risk by not providing adequate employee incentive. No one wins with a toxic cap table. (You can find some great stats on founder ownership here.)

Don’t compete on valuation

You will only create stress if you measure your success by the amount you raise and the price of equity. There will always be someone else who raised more. Some startups are in a hotter market and can command better pricing through demand. Others simply need more working capital to get going. Think of valuation as a measure of your cost of capital. While you would always like a lower cost (i.e. higher valuation), lower financing doesn’t mean the business is superior; it’s just a reflection of the business risk. Fundraising is a finite period in a startup’s life, and in a few months no one will care. Instead you should be competing on the investors you’re able to bring into the round. Optimize for backers whose brand is so strong and provides validation.

Know your sh*t

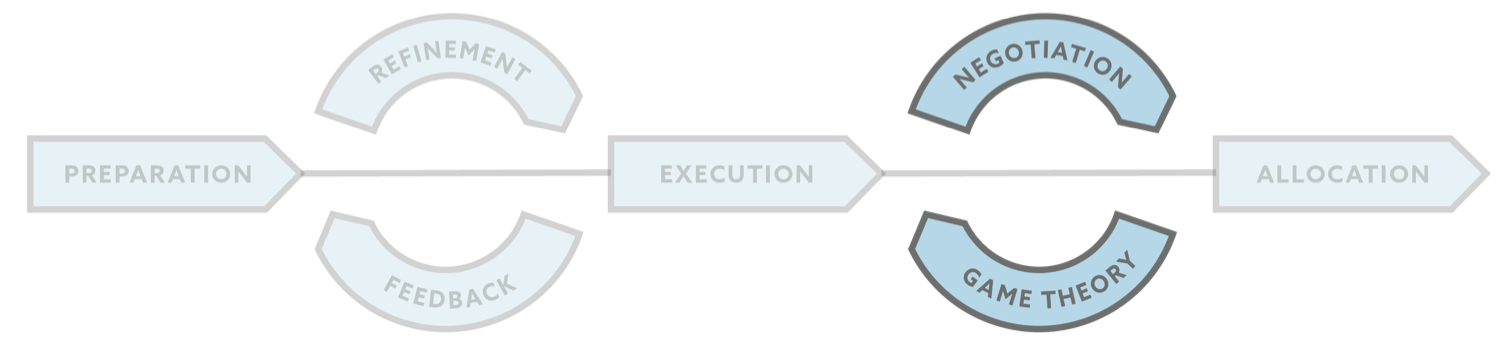

The first thing you’ll learn in any negotiations class is that preparation is the single biggest driver of success. You have to assume any investor will have many more years of experience than you in structuring deals and will be more skilled in this arena. Even the odds by doing your homework. Here’s a list of stuff that you should have/read:

Terms: There’s a lot of jargon in term sheets, so familiarize yourself early to determine if your offer is in line with the market. Venture Deals by Brad Feld is a must. (Pay close attention to liquidation preference, pro-rata and anti-dilution rights. There are clear market norms on these three, but investor opinion does vary.)

Employee Option Pool: Every investor will require you to create/top up a portion of equity for employee incentives packages. Push really hard to keep this at 10%, max 15%. It’s also important to understand if the top up takes place before or after the financing.

Financial Model: While your forecasts may be (are) a total guess at this point, you still need to back up your estimates with logic and data. I recommend this post for insights (written for SaaS, but the lessons hold).

Cap Table: Most lead investors will likely provide a cap table with any term sheet, but it’s imperative that you fully understand the math and ensure it reflects your business. Ownership can get pretty tricky when you start layering on convertible notes, employee option pools, etc. so you can’t start too early. I like Captable.io for tool building and this Equity 101 post for guidance.

Competition is your friend

The second thing you’ll learn in any negotiations class is leverage is key to good deals, and it comes from having options (a.k.a BATNA). This is why we covered pipeline and batching in previous posts. Nothing will help your negotiation position more than having multiple term sheets. This leads to better terms, superior pricing/valuation and more impressive co-investors. The venture capital asset class is one dominated by behavioral finance, where herd mentality and FOMO are the standard. If you have multiple offers, then well done! If, however, you only have one, then you’ll need to make a judgment call and play the game on the field. With just one term sheet, your BATNA will be to continue fundraising. There’s no shame in turning down a term sheet if it’s not right for you, but it’ll be back to square one.

Stamina (again)

This is the third time I’ve mentioned stamina in this series, and it’s as true now as it ever was. Negotiating is hard. A lot of people hate it, and that’s why there are agents in the world. There’s a wealth of great Negotiation 101 books (here and here), so I won’t waste your time with that. It’s difficult to bargain over competing interests while building a relationship for the future. The best advice I can give is to be transparent, communicate your interest and be open to listening to the other side. An investor wants the deal to work as much as you do. Be professional and act like an adult. This deal sets the foundation for your business relationship, so playing games now will only screw you over in the future.